Victorian Funerals & Mourning

Death In Victorian Times

Today outside of certain professions, it is rare for people to actually encounter death. It normally happens quietly in a hospital with family and loved ones being told after the event. However, only a century or so ago, things were very different. Despite all of the medical and technological advances of the Victorian era, the populace was still very much surrounded by death. Infant mortality was incredibly high, while life expectancy, especially in some major cities was frightfully low. On top of this, most people died in their homes, often the home they were born in, often the same home where they watched their parents die. It was natural not only to see death, but also to see the full decline of someone towards death.

Mourning In The Victorian Era

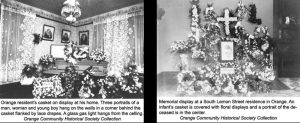

The mourning process was strictly kept in Victorian times. A wreath of laurel or boxwood tied with crape or black veiling was hung on the front door to alert passersby that a death had occurred. The body was watched over every minute until burial, hence the custom of “waking”. The wake also served as a safeguard from burying someone who was not dead, but in a coma. Many families would host wakes in their homes for up to four days and the tradition of bringing fresh flowers to funerals stemmed from a time before embalming. Flowers were a way of masking the odor of the decaying corpse.

Caskets were often placed on a cooling board which resembled a tub or crate of ice under the body to slow down the decaying process. Clocks were stopped at the time of death and mirrors were either draped with black cloth or turned to the wall so the spirit of the deceased could not get caught in them. The dead were carried out of the house feet first, in order to prevent the spirit from looking back into the house and beckoning another member of the family to follow him. Family photographs were also sometimes turned face-down to prevent any of the close relatives and friends of the deceased from being possessed by the spirit of the dead.

Turn of the Century Funeral Processions

When the time for the funeral came, the casket was transported on a hand wheel bier, or in a carriage built hearse drawn by black-plumed horses. The mourners followed the coffin from the house on foot or in mourning carriages, of which there could be many due to most people not owning their own vehicles. A long funeral procession made a grand sight, members of the public stopped and bowed their heads as the carriage passed by. Motorized hearses, forerunners of those used today, came into use in urban areas during the 1920’s. However the horse-drawn hearse was still in frequent use long after this. Most burials took place in nearby Santa Ana Cemetery.

Post-Mortem Photography

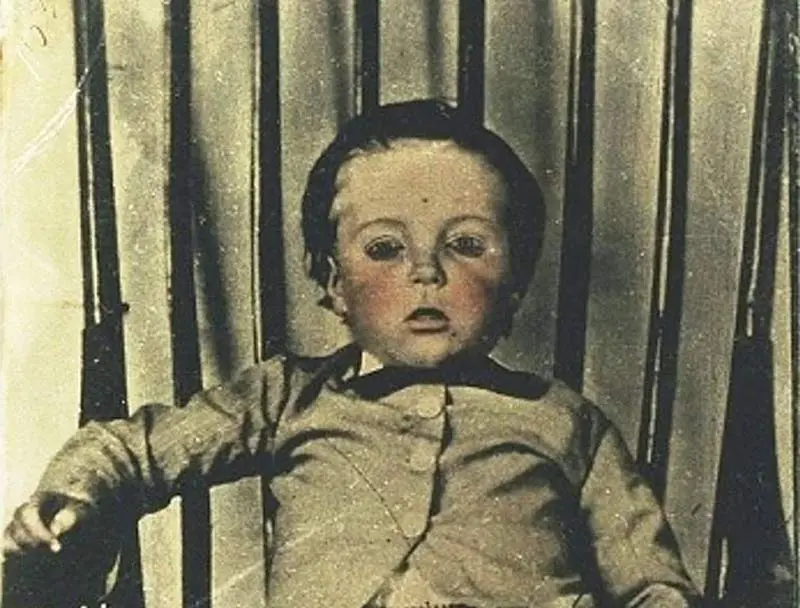

In the Victorian era, the infant mortality rate was high and in fact, life expectancy in general was far less than it is today. Parents may not have had their child photographed while they were alive. In the event of a sudden death, the family would have rushed the body along to photographers to have a photograph taken as a reminder of their child.

Some of these photographs were tastefully done showing the obviously deceased child laying on a bed surrounded by flowers and apparently asleep. However if the family did not have a photograph of their child or family member while they were alive, they would instruct the photographer to give the impression that the deceased was still alive at the time of the photograph.

One of the first parts of the body to deteriorate after death are the eyes and many photographers became experts at painting false eyes on to closed eye lids. Some photographers were more skilled than others at this macabre task. The picture to the left shows how the skill has been applied and the photograph has even been tinted to achieve a more “alive” look.

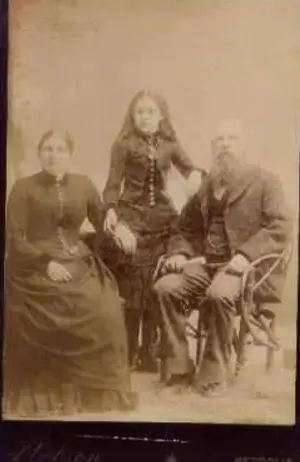

When the deceased was older, much greater ingenuity was used to give the impression that they were alive in the photograph. Frames were built to support the deceased and supporting rods would be inserted through the back of their clothing. If you look closely at the photo to the left, you can see a base behind the girl’s feet and a post would go up from that with clamps at the waist and neck and the clothing would b

e open at the back. The arms would have stiff wires running at the back to hold them in place. Also notice the strange placement of the hands. The pupils are painted on the closed eye lids.

These photographs were a common aspect of American culture, a part of the mourning and memorialization process. Surviving families were proud of these images and hung them in their homes, sent copies to friends and relatives, wore them as lockets or carried them as pocket mirrors. Nineteenth-century Americans knew how to respond to these images. Today there is no culturally normative response to post-mortem photographs.